Dog Sledging

We should say something about this because a few years ago the bureaucrats decided to ban all sledge dogs from the Antarctic. A reason I was told was that one might break loose and kill a penguin! Three parties once did a total of 5000 miles in one summer at a cost of 54 pemmican blocks a day costing about $1 each. They now use either ski-doos or turbine helicopters at about $3000 an hour. Consequently not a great deal of field work has been done since. I was never one of the world experts but I have been dog-sledging quite a few times since 1955 and have covered more than a few thousand miles. It used to be claimed that it took a year to train a dog driver but I have trained a good one in two weeks. My own experience was that there was a vast difference between being in front and being No 2 following! But then I learnt “When in doubt, trust your lead dog!”

A well-behaved team resting. We are close to One Ton Depot out on the Barrier. Scott, Wilson and Bowers are buried not far away. Dismal and Fido who led all through 1956-7-8 are still in the lead in 1959. The two rear dogs are in harness for only the 10th time and have settled down to be good hardworking huskies. Zaza with her tail over her nose did the entire Northern Journey three years before as a mere “teenager”. A well-behaved team resting. We are close to One Ton Depot out on the Barrier. Scott, Wilson and Bowers are buried not far away. Dismal and Fido who led all through 1956-7-8 are still in the lead in 1959. The two rear dogs are in harness for only the 10th time and have settled down to be good hardworking huskies. Zaza with her tail over her nose did the entire Northern Journey three years before as a mere “teenager”. |

One may not think that taking a 12ft sled of hickory and ash, lashed together with white whale strips, hooking nine dogs in the front on a centre trace, loading a half ton of supplies on it and taking off for a few months would come under the heading of “fun” but it did.

Some very famous people, (leaving out the Eskimos who have been doing it for about 2,000 years, and Peary and Cook) including Gino Watkins, Quentin Riley, Spenser Chapman, Cortauld, John Rymill, Bingham, Mike Banks, Richard Brooke, George Marsh, Butler, Kevin Walton, Ray Adie, Bunny Fuchs, Ken Blaiklock and hundreds of others, went off in ancient schooners and fishing boats to the Arctic and Antarctic, found a bay, built a small hut and lived there for 2-3 years, mapped the country in, looked at the geology and wildlife, hunted bears and seals and usually survived, but why? Well, one of the reasons was the fact that you had the exhilarating experience of travelling by dog sled.

Blue Glacier after a storm has blown all the snow away- much rougher! Temp. is about -30 (see the long shadows, it is September). In about 30 miles of this I think we broke one deck panel. But on snow we had to ice the runners. Greenland sleds are shod with steel. |

The best is to travel with three dog teams and four men, then you carry a ton and a half and have an extra man if something goes wrong. On reasonable going you can guarantee to do 20-25 miles a day, you can cross very thin ice and pack, you can bump over pretty bad sastrugi that would stop a sno-cat. It costs a block of pemmican per day per dog and few things ever break. You can go out 800 or a thousand miles and come home again given a bit of support in carrying supplies.

Amundsen took dogs to the South Pole from Bay of Whales in 1911. He averaged 20.8 miles per day, across the Ice-shelf, up the Axel Heiberg Glacier and across the ice cap and back.

In 1957-8 Dr George Marsh and Sir J Holmes Miller (as he became), sledged even further, (about 1800 miles) at an average of 22.4 miles per day from Scott Base, over the Barrier, up the Skelton Glacier, out to Depot 700, back east towards the mountains, surveyed the Miller range and came home. To my knowledge that was the greatest sledging journey ever. Amundsen has some depots laid before and then killed half his dogs on the way home. George and Bob had some depots laid and at least one flown in, but brought every dog home.

The same year our Northern Party did a mere 1600 miles altogether including Spring journeys but we did a lot of survey work and walked maybe another 500.

A seal is butchered by Richard Brooke for some hungry dogs, (plus some seal liver for us, see on the right!) Spring Journey, at the Stranded Moraines, Sept. 1957 |

Living off the land as always, is OK for a month or so but is rather lacking in intellectual stimulation. Conversation dies completely. You do not waste time saying:

“I say I think I see a seal behind that pressure ridge. If I sneak up and get him would you be so kind as to bring up the dogs and we can get fresh meat for the whole party, we are rather short you know!” and he does not waste time replying:

“I say what a jolly good idea, do be careful my dear chap he may slide back down his diving hole if he hears your bloody great clumping feet!”

Instead of which you catch his eye, point with your chin and he briefly nods, all else is understood, it has all been done a few times before.

Not a blizzard yet, but a head wind of over 20 knots working up. About 200 miles south on the Barrier, the dogs get what comfort they can on a break. See Dismal looking ahead to see what is coming! |

Setting up camp after a few weeks on the trail becomes a routine. As evening approaches you hold up an arm to warn the sleds behind, then swing left, “Aaah, dogs, lie down!” The other sleds also swing left en eschelon. You drop in a picket to hold the sled, walk forward unlashing the tent which lies on top, take the shovel the dog span and your ice-axe and walk to the front of the team, push your ice-axe through a ring at the front of the centre trace so the dogs cannot move. Dig two trenches and bury the wooden ends of the wire span. Unclip nine dogs and clip them to the span. They all yelp and howl, knowing feeding time is coming up. Back to the sled, take nine block of pemmican and throw one to each. There are nine incredibly rapid gulps and they are gone.

Fido says: “Gee! How nice of you to notice me!” |

Pull out the tent, stand it four square, throw in your sleeping back and the cookbox and tucker box. Your tent mate comes up carrying the radio and vanishes inside, his dogs are already spanned and fed. He slaps down the billies to be filled with snow, and there is a roar as the primus starts up. You dig snow blocks and pile them on the tent flaps, knock in pegs and tighten guys. The sled is packed, skis slid underneath, the centre trace is coiled on the front of the sled, (if left out it may freeze in), a final pat for the dogs and leaving them to curl up, tail over nose, you enter the tent and pull off mukluks and hang the felt liners and anorak at the tent peak to dry.

Your sleeping bag has been unrolled and you sink back in comfort as your companion silently hands you a mug of tea. You sip in silence, then he bursts out in one of the few conversational gambits allowed. “I say, dogs went rather well today, don’t you think? Twenty six miles on my meter, and those few miles of breakable crust slowed us a little. I must say, my lead dog is shaping up rather well!” “Aye, we were lucky that breeze died!” And one relaxes in total peace and quiet, the only sound being a patter of drift on the tent, or a yawn from a dog.

There have been some long trips done by snocat over the icecap but not anywhere near mountains. I do not know of a large scale geological survey being done using ski-doos though one party took them up the Shackleton Glacier and another up the Darwin and McCleary. At any rate they bore me silly!

In general the words of command used to drive dogs are Labrador Eskimo, because that was where Gino Watkins first drove dogs in about 1925. So you scream “Huit! Huit!” to go ahead, “Ahhhh!” to stop, “Rrrrrrrrrr” for left and “Auk! Auk!” to go right. A good lead dog soon works out where you are going, he goes to one side if there is a crevasses below and he will find a way through a pressure ridge without being told.

A replete and smug-looking Dismal. He has carefully left the blubber for tomorrow, but a good driver takes it well away and gives it to the skuas, or feeds it in small bits. Otherwise dogs tend use it as hair lotion and roll in it, matting fur, so that it no longer will keep them warm (and looks horrible). A husky with blubber in his fur is the sign of a bad/careless doggoe. A replete and smug-looking Dismal. He has carefully left the blubber for tomorrow, but a good driver takes it well away and gives it to the skuas, or feeds it in small bits. Otherwise dogs tend use it as hair lotion and roll in it, matting fur, so that it no longer will keep them warm (and looks horrible). A husky with blubber in his fur is the sign of a bad/careless doggoe. |

Gino was drowned when in his kayak near a calving glacier in East Greenland hunting seal for the dogs. It is thought that a piece of glacier fell and rolled him over unexpectedly as he had perfected the technique of rolling his kayak either by hand or paddle. I have never rolled a kayak myself but pretty well everything else I know was handed down to me by successive generations of polar people from Gino Watkins.

Dogs can jump quite wide crevasses, or split to one side and run across a snow bridge. You then give a “heave” to get the sledge over before something falls in, hang onto the handle bars and jump yourself. It may sound a little dicey but sometimes it is either that or turn back. Sometimes a dog fell down a “hole” but we always got them out.

Without the husky dog, the polar regions have changed forever. There is no adventure, it is boring and mechanical, self-reliance is no longer needed, a machine takes you there, another machine tells you to come home. The people you meet are, I fear, quite ordinary. It did not used to be that way; if they were not outstanding they would never have got there.

Odd that it never occurred to us that our way of doing things would not go on for ever,

However one must admit that some of vital skills one learned such as sewing up a dog-harness, patching a tent, navigating by sun compass and bubble sextant or breaking trail in soft snow by running like hell on ski or snowshoes do not seem to be in great demand these days, and the few of the old dog-sledders that survive seem to be mainly unemployed. Even mapping country by squinting through a theodolite seems to have been given away.

Huskies have certain rules such as “Never bite a bitch or a young dog even he has pinched your pet seal bone. Never bite the boss unless he has just stood on your foot. Always do your share of work or I will get you. Keep your distance or I will take your ear off, (notice how they are spaced out in the pictures). Die if you must but PULL!”

Huskies make people seem pretty limp.

… And the people who drove them

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

||||||

Aircraft

| Constellation The Super Constellation was a big advance on the old transport planes such as the Globemaster. The USN “Connie” was fast and comfortable, and in 1959 it was sent down on a special flight to bring the geologists Dr Gunn and James Lowery home after both were injured in a crevasse accident. |

|

|

| Hercules C-130The workhorse since about 1963, the “Hercs” fly fuel, supplies and more than 3000 people a year to McMurdo, the Pole Station as well as to many remote field parties. Only ski-equipped Hercs land at the Pole. The RNZAF makes half the flights in from New Zealand in the same aircraft. |

|

Ships

| In 1955-6 we had no less than 5 icebreakers, Two were Coastguard cutters, painted white with 6 diesel-electric engines. Here the “Eastwind” lies alongside the ice. |

|

|

| In 1956 we were breaking a channel closer to Hut Point in the “Glacier” when these two ships began calling for help. The “Wyandot”, (cargo ship) has a large piece of ice against her screw and could not move. We (in the Edisto) washed it away with our propellers. Note the gun platforms; she was a wartime freighter, read more about wyandot by clicking here

Then the Fleet tanker “Nespelen” began yelling for help. An icecake not 30ft long had been drifting slowly past. The ship began to list, a rent 20ft long had been torn in her side, an engine tilted over and 32,000 gals of aviation fuel was lost. No ships were ever lost, but some got home on half a propeller and with large cement patches over rips in the hull. |

|

|

| The “Glacier” (9000 tons with 8, 2000 hp Fairbanks-Morse engines) opens up a passage towards Hut Point. White Id and Minna Bluff in distance. Once we hit a small bergy bit and half an hour later the Bosun reported 15ft of water up forward. We ran her up on the ice to find a 14ft rent in 5/8″ steel hull overlain by 1 3/8″ in armour plate. The Glacier could break bay ice up to 10ft thick. |

|

|

| The icebreaker USS Glacier returns homewards in March 1956 in the Ross Sea after a roughish night with much freezing spray flying about. >> |  |

Building the first garage in the Antarctic, Bates and Ellis in late Feb, 1957. |

Bases in the Antarctic

You don’t last long without some form of shelter.

Unfortunately, the materials all have to come from overseas and there are precious few days with ideal conditions for building in. Our bureaucrat organisers decided a garage was not necessary. Unfortunately we had 5 tractors and two weasels which needed maintenance and constant repair and essential things like fuel drums had to brought up from the dump right through the winter. Bates and Ellis showed a bit of good old Kiwi engenuity, fabricated trusses by welding waratahs, made walls out the dunnage from packing cases, built a blubber heater stove from drums and it was used for the next ten years. The “Caboose” was built in it and the tractors modified, so that without it, Sir Edmund Hillary would never have got to the South Pole.

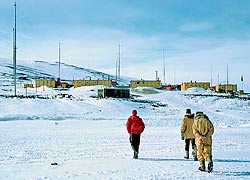

| The first sun falls on Scott Base at McMurdo in early September 1957 after 4 months of darkness. Winter blizzards have packed snow about the covered way. See the home-made garage covered in green canvas on right. >> Vern Gerard, IGY seismologist walks up a snow ramp. Observation Hill trachyte dome in distance. The Yank Camp is over the pass. Now all is gone except the mess hut, second on the left joined by the covered way to the bunk huts and the scientific hut at the far end. I stand on the roof of the Sledging and # 2 generator hut. >> |

|

|

| The new hangar built at Scott Base in 1959 to take the Beaver and the Auster. The Beaver was crashed that year due to some sloppy airmanship, since when the hangar has been used as a store. Two garages have been added to the sledging hut. |

|

|

| The green hut is the Beaver’s box covered in canvas where the Beaver (plane) spent the winter of 1957. |

|

|

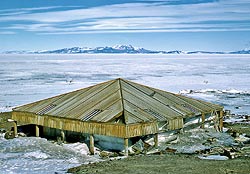

| Scott’s 1901-03 hut. It was bought as a prefab in Australia, in case the “Discovery”, which was moored alongside, caught fire or had some such disaster. It was full of ice but I began digging it out in 1955 and it has since been restored. |

|

|

|

|

||

| About 1961. Diesel fuel cost $5 per gal at the ice, and the nuclear plant was to save money. It did not work; radiation caused bubbles of nascent O2 to form on the fuel rod casing forming an insulating barrier. The rods repeatedly overheated and the plant automatically shut down each time. Why this hasn’t happened at other NP plants I do not know. So it was dismantled. |

|

|

| Jamesways are an insulated shelter which can be erected quickly, sometimes used in semi-permanent field camps. |

|

Foot, Ski and Manhauling

In the absence of dogs, travel slows down considerably. In the Dry Valleys one may be forced to backpack for a few days, but the amount of extra clothing, tents, radio etc. makes the loads heavier. In New Zealand one may back-pack for two weeks, even a month if one is prepared to accept a spartan diet and cook on wood fires and drink milkless, sugarless tea. In the South large amounts of fuel are carried. On glaciers of gentle slope one can manhaul light sleds with 2-3 weeks supplies without too much difficulty, but a slower and more monotonous form of travel cannot be imagined, you MAY make 10-12 miles a day but in soft or rough going it can be much less. People have crossed the continent solo with a man-hauled sled, with the aid of parachutes to help sail, and usually frequent aircraft lifts. The invention of the horse collar doubled the efficiency of the horse but no such invention has been made for people, we are a most ineffective draught animal.

On snow, even pulling a sled it is usually better to wear ski, even sinking in a couple of inches is tiring, sinking in a foot is B***y tiring. Sometimes on icy sastrugi, the skis have to be put on the sled, sometimes one has to wear crampons as well.

Skidoos? I cannot comment. My one day on a skidoo bored me to tears, the reek was appalling and the racket more so. Deafness from broken skidoo mufflers is now an occupational hazard for the Inuit (Eskimos).